|

| Two-room schoolhouse François Bourassa and his sons built in 1886. |

SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION: On January 26, 1886, our school municipality voted overwhelmingly to borrow $4,000.00 to build three schools, one in the village (no.1), one at our homestead three miles northeast of the village (No. 2) and the third three miles southeast of the village (No. 3). In March, they announced bids for the construction of the three schools would go to one contractor and, according to the specifications, the keys to be hand-delivered on October 1 for the opening of classes.

That same day I said to Abdalah and Hector, "I think we should make a bid ourselves." They agreed. I was given a copy of the specifications and began the calculations of all the equipment needed for the three constructions. Armed with these calculations and specifications I went to find Mr. Rolston from Kilarney [Manitoba] (a French-speaking wood merchant). He devoted himself to my calculations for an entire day, smoothing out and making some additions, and then added 20 percent to the capital for accidentals (something I had done for only 10 percent). I had a bid prepared by Telletson, leaving blank the capital amount which I added myself, and submitted it to the board on the morning the bids were to be opened. The board was composed of Father Malo and two Anglos. We couldn't hope for any favors. It was certain that in the event of a tie or even roughly close to submissions made by English-speakers, we would be rejected. The board opened the meeting and requested the clerk submit the submissions to them in the order received. The first one he introduced was $2,800. He opened the second, which was Ried and Rowson's $2,375.00; and then opened the third and final one, mine at $1,995.00. The two English-speakers (Taswal and Smith) stared at each other for at least a minute. Taswal turned to Ried, saying, "It’s impossible. There is too much difference in the submissions to ignore. If Mr. Bourassa is willing to make a contract by giving the guarantees, we will give to him." I told them, "It seems to me that the guarantees are easy to give, because in your contract you will have to advance to the contractor one third of the capital, in bulk, and the rest as the work goes on. It seems to me that it's possible for me to give you security for $6 or $7 hundred to prevent you from having ‘a fever’." Taswal said to me, "Will you give us your personal property for security?" "Yes, " I answered. “If it's not enough, I'll give you more." They called on Telletson to have the contract prepared. Arriving to give them security, I said to them: "First take my teams of grey mares harnessed to my wagon." Taswal said, "I think we've had enough." Father commented, "If Mr. Bourassa can’t meet the security, I will fill it in." The contract was signed. It was easy to see that to have the contract, I had to be very tight, a $100.00 lower even, we would not have had it. I was happy to accept Abdalah and Hector as partners. For this we needed an act of association. We went to Hulman's house and had this act prepared. By this act, I became the main contractor. In my absence it would be Abdalah. Any hires would be made by me with their approval. When I worked with my horses, I would be paid $5.00 a day. When I worked only with my hands, $3.00 a day. Abdalah, with his hands only $2.75, and with his oxen, $1.50 more. Hector $2.50 and with his oxen $1.50 more. We paid ourselves wages every week as we would with outside labor. If there was a deficit when the work was finished, we had to fill it with a comparable percentage of what each of us contributed to the work. If, on the contrary, once we finished, we had money left, we would share it, divided by the amount each contributed, always making a division of the block gains of the three partners. This act completed, I signed it. Abdalah too, but Hector didn't want to. Yet he worked there as if he had signed.

|

| Martineau had bought out Brunelle's grocery business. |

When our construction was completed, and even before, he criticized our work as if he knew something about construction, in order to embarrass me on the delivery of the three schoolhouses. Fortunately, I was dealing with a group more honest than he was. Examination of everything was done with great care because Martineau’s criticisms had circulated. The group unanimously complimented my work, to the shame of Martineau, who had made false allegations to the directors themselves.

|

| Hector and Horace Bourassa |

ABDALAH DECIDES to REMARRY: Around August 8 [1886], Abdalah [whose wife Josephine, had died the previous November 12th] asked me if he could get married. I was surprised. "Your mourning is not yet over, so how could you spend precious time with such a person. Ah, ah! I did not give you any time off [from the school constructions]. With the deceased you sometimes whined. But this time if you take this woman you will have your hair pulled out and grind your teeth more than you will laugh. It's none of my business, so don’t talk to me about it anymore. I'm telling you she doesn't suit you. Now that's it." [Abdulah was 29 years old.]

|

| Lindorf Bourassa (1866 Quebec-1946 Radville, Sask. Canada) |

|

| Philomene Martin (1865 Quebec-1947 Radville, Sask. Canada) |

About two hours later Father Malo took leave. Over the following four hours Abdalah disappeared. The next day I learned that he had married Véronique Paul, a neighbor, the same one he had talked to me about the week before. The next day he came to tell me all this and that he was going to relocate to his house. "Definitely," I said, "you have nothing better to do." He settled down and took his little Stanislas [his four-year old son], who was slightly better [from his skin infection] (the baby having died a few days after his mother the previous November). My poor wife felt some relief at the departure of her son and grandson. Unfortunately, this riddance did not last long. This child was too much of an embarrassment for Veronique. Every day, she would bring him back. In December, with almost all Métis moved for the winter into the woods, there was no life for Veronique here on the prairie. They too had to move to the woods [at Turtle Mountain]. What was done was done.

[I can find no photo of Abdulah or of Véronique Paul, or of Abdulah's son Stanislas. The Paul family were Métis (part French or Scottish and part Native American) and were some of the earliest residents at St. John. Here is a photo of Véronique's younger half-brother Alfred "Fred" Paul, his wife Clemence, and their child Clora, c. 1903. Véronique appears to have died childless. Abdullah married the widow Ellen (Brunelle) LaChapelle in 1895 and had numerous children by her.]

A GUARDIAN FOR ABDALAH’S SON: In March 1887, Abdulah came home complaining to his mother, telling her that he was afraid for Stanislas’ life, that Véronique hated him enough that he feared accidents. His poor mother didn't know what to say. In the evening she told me everything and told me that she would rather take Stanislas back than risk what might happen. The next day I went into the woods and said, "Tomorrow night go home. My intention is to take your child under our protection. But to do that, I intend to establish conditions. Your brothers and brothers-in-law will be present." [Lumina had recently married our great-grandfather Omer Charbonneau.] "That's good," he told me. I had Bruneau [Bruno] and Méline Charbonneau [Omer's brothers] ask him to come, as well as Lagassé. All were present on his arrival. I told them that my wife and I were determined to take the boy under our protection, but I wanted an assembly of relatives to decide on a guardian to be appointed. Moreover, let an assessment be made of what Abdalah had on hand at the death of his late wife, and that it should be decided and understood that the guardian will have custody of the small share belonging to the deceased. Those assembled understood perfectly. (I had told them from the beginning I did not want to be part of their decisions, but wanted them to understand the burden we were accepting.) Proposed by Bruno Charbonneau, seconded by Lagassé, that F.X.A. Bourassa, grandfather of little Stanislas Bourassa, is the guardian of the said child, passed unanimously. On this resolution Abdalah became the subrogor guardian [the one yielding his parental rights] of his child.

Then they did the evaluation. Abdalah listed the articles. The deceased [Josephine] had nothing to do with the entrance to the homestead [she had remained in Montreal until later]. They rated the small [spinning?] wheel and furnishings at two hundred dollars. So, there was $100.00 for the child to be granted to the guardian. Almost all of them seemed perplexed about this decision. Lagassé said, "My friends, do you not find that the amount is very small to be offered as a reward or as a gift to the guardian, who bears such a burden, even if this child would remain with these protectors until twenty-one years, good and obedient even, he will never have half of what it will have cost, until the age of 15 to 16. (I've remembered these words many times since and always will.) How many tears this child will make his poor grandmother and his aunt Lumina shed.” I, also, became angry with him [Stanislas] many times. When he was twenty, I had brought home from the village the side of a buggy to replace one that was broken in two. I put it on my workbench, planning to work on it when I had time. One day it was raining, and I went to finish my work, only to find he had cut in half the new side I’d brought, just to get at me. That and similar things he did to me during life. It is always an arduous task for parents to raise a large family. I heard Maman say, "I never had more misery from my entire family as we did from this child." A father and a mother try to forget the miseries endured during the raising of a family. But events such as these are difficult to forget. [Stanislas eventually left his grandparents' farm, for he appears in the 1906 Souris, Manitoba census with his father, stepmother and numerous half-siblings. He does not appear in the 1900 U.S. census in the Turtle Mountain Reservation census in which Abdulah was listed as a 'hotel man'. His children are listed as being able to read, but not to write. Stanislas appears never to have married; he died in 1927 in Weyburn, Saskatchewan.]

YEAR 1887: My 1886 seed was 22 minots of wheat, 40 of oats, of 15 of potatoes, 8 of barley, of a good garden. Yield was small: 9 minots per acre for wheat, 39 for oats, 18 for barley, 215 for potatoes. Gardening was average, too. But all were of good quality. The winter began very harshly on November 15th, which gave us a cold of 17 to 32 below zero, continuing to vary throughout the winter. [This was the terrible winter, called the Big Die-Up, that destroyed the great cattle herds of the West.]

|

| Waiting For A Chinook by Charles Russell |

Work on the earth began in April 1887. But we had a variable time. On the 8th I planted 12 minots of wheat and the 20th another 12 minots, [all of] my wheat seed for the year; oats, 32 minots, barley 12 minots, and 10 of potatoes; a good garden.

|

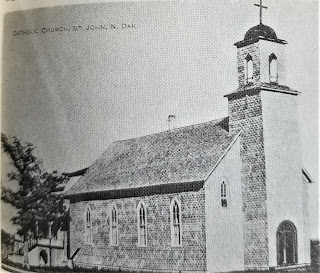

| This is the church where my dad, Al Charbonneau, and his cousin, Red Charbonneau, were baptized. It was replaced in the early 1950s by the present church |

Sunday, the 24th, Father revealed that plan to the parish and encouraged those, whose finances were too embarrassed to contribute money, to show up the next day in order to do the work he’d just explained. Indeed, the next day there was confusion regarding the appropriate places for everyone. They succeeded over time. Father made arrangements to have me oversee the work. “Father, I can't,” I protested. “Building the schools made me neglect my farm work. And I plan to build a barn this summer. Maybe my sons can do it. Abdalah or Hector can, with my help from time to time. But none of us wants to supervise this work for less than two dollars a day." Old Jos. Desrochers offered to manage the laborers for a dollar and a half, so he was entrusted with supervision. In June the body [of the church] was elevated . Prior to that date, there had been disputes among the trustees regarding supervision and some points on construction. So much so that [Bruno] Charbonneau withdrew as a trustee by resigning.

After the body of the church was elevated [likely the framing was put together on the ground, then raised like a barn-raising], the walls were constructed (30 x 60 and 22 feet high), without any bracing. [Being made from trimmed logs, cut to fit, the walls were probably built from the ground up.] Martin and I protested, declaring that these large sections would not stand up if they were not solidly braced [with joists]. They ignored our warnings and continued. They had not finished before a great southerly wind arrived, blowing from one side to the other while they were working. They hurriedly braced in several places, managing to keep the walls up. When they had finished tucking, they began to lift the attic as an ordinary barn roof was lifted, having removed all the large [joists or rafters] that made the construction solid, having put only one small [truss?] at two thirds of the height of the rafters with a small cross board, above the [truss?] in the head of the rafters. [Translating French language construction lingo is difficult for the Internet application and for me.] My plan was much simpler, and did not cost half of what the avalanche of wood that old Desrochers added to it, knowing no better than anyone. Martin, seeing this, came to warn me. We summoned the trustees to meet that evening. All were present (minus Charbonneau, no longer wanting to take part). We told them that the fault was in removing the stabilizing force [trusses?] that held this building upright, that the original plan had what it took, no more, no less, to create a stable building. It was useless. These old men knew nothing. Immediately, Martin and I submitted our resignations, no longer wanting to appear to support what was happening. I withdrew, washing my hands of everything that was about to happen. I did not regret my warnings. I had done everything I could to make sure everything was fine. It was without remorse that I withdrew.

They continued and covered the roof. In August we had a strong southerly wind that shifted the building by more than 6 inches. It would have fallen had they not quickly braced six 30-foot-long logs on the north side, holding the church upright. At the beginning of September, we had a strong northwest wind that affected the south side, helped by the braced logs set to the north side. They noticed just as the church was shifting on the south side. Quickly they put logs on that side, as they had in the north. Our good Father Malo began celebrating Mass in this rickety castle, and moved into the addition, his future residence. It was clear as daylight, the church could not last long.

|

| John Ireland (b.1838 Kilkenney Co., Ireland- d.1918), Archbishop of St. Paul, MN |

|

| François and Marie Bourassa |

|

| Alcide, Lindorf, Horace, Hector, Alfred Bourassa. Abdullah not shown, so photo probably taken after his death 1910, possibly 1918 at their father's funeral. |

Georgina (Bourassa) Durocher died in 1944 in Kenniwick, Washington.

As for our great-grandmother, Marie Elisa Lumina (Bourassa) Charbonneau, she died in Seattle, Washington, in 1952. Here's a photo of Lumina and her family I haven't posted before. You'll recall she lost our great-grandfather Omer Charbonneau in 1913 at St. John.

|

| c.1936. Dad's father Alfred and Red's father Charles in back row. |