The final destination was Jackson Field, Port Moresby, Papua, New Guinea. Officially, the Battle of Port Moresby was ongoing, with Port Moresby still being attacked, but the tide was turning. HERE

Mom wrote on June 9th, acknowledging getting Dad's V mail letter from Hawaii (Victory Mail was written, censored, copied to film, and printed back on paper when it arrived at its destination). She thought Hawaii was his new station and asked about the beautiful girls he must see there.

|

| Jeanne Raney (1925-2014) 1944 |

June 20, 1943

. . I received you cablegram last week darling. As you know I'm learning to be a telegraph operator. We-ll every day I go up to the telegraph room to check the incoming telegrams for an hour. I pulled one telegram off the crane that just came in from San Francisco. The ink was still damp on it. I looked down and saw Nora [Street] on it. So-oo-o Thought I to myself. "Hmm, maybe I know the people." So I glanced at the name and honestly darling you can imagine my surprise. I just stood there and gasped. I just couldn't seem to understand that it was for me. It was sweet of you darling, to let me know that you are all right. I haven't gotten over the thrill yet . . .

|

| Mom's oldest sibling, Paul Raney (1913-2005) |

|

| Junice Moe Raney (1916-2012) |

|

| One of the two B-24s on which Dad was a crew member. The other was called Ace in the Hole, but its photo has disappeared. I don't recall which ship crashed. |

July 6, 1943

. . Now that I am stationed somewhere in New Guinea [unable to state exactly where], and on a permanent base, I can write more often. I haven't yet received any mail from the States, but I expect some within a week or two. We have been bombing the Japs quite often, and doing a very good job of it, starting a lot of fires - that's all that we can see because all our work is at night so far . . . [They were bombing Japanese ships in Simpson Harbor at Rabaul, and other targets.]

|

| Simpson Harbor, Rabaul. Dots on water are Japanese ships. Yellow square is target. From Dad's scrapbook |

. . Paul has just come back from Liverpool. Uh-huh. He's in New York now. But he will soon be called back to ship. He's going to get another commission of Lieut. That's all double-talk to me. The only thing I can understand is army and when anything concerning the navy comes [up] with the conversation I'm completely lost. . .

|

| I recall the grass skirt, which he brought home, being a deep burnt sienna color. Photo taken at Port Moresby, 1943. |

August 29, 1943

. . Yesterday I became a full-fledged operator. Before, I was merely going to school, trying to cram into this brain of mine the essentials of telegraphy. And yesterday I graduated and now I'm a junior operator. Pat me on the back darling - I'm surprised myself.

Friday I received a letter from Paul. As you know he is now in New York, but he is shoving off soon. He is now commissioned to a Lieut. which is equivalent to a captain in the army. We are quite proud of him. He deserves the best of everything because his life has been one continuous line of dirty deals and bad luck. So drink a silent toast to him and keep your fingers crossed because this mission is going to be more trying than ever before. . . [You can read about Paul Raney's adventurous life during the war HERE]

Mom began working swing shift - 3:30 to midnight - and lest you think the streets of Spokane were empty when she got off work, think again. Men in uniform crowded the sidewalks, lonely to talk to a girl. They came from Farragut near Sandpoint, Geiger Field, Ft. George Wright, and off the trains en-route to somewhere else. One night, a couple of Australian soldiers approached her and her workmate, Monnie, who boarded next door. "Kin I boy ye a cuke?" one asked. "A what?" she answered. "A cuke . . . ye know . . . A Cuka Cula." Because it was wartime, she wrote, she got two days off a month, often on a Sunday, during which time she would become reacquainted with "the folks."

Sept. 20, 1943

. . . I'm sending you some things that I think you need - I'm taking advantage of the Christmas mailing time. As you probably know, they won't let you send anything overseas without a permit. It's easy to understand that because every inch of valuable space is needed for the essentials that will bring the end of the war nearer . . . I'm very proud of [Paul] - but I get such an awful lost feeling when I come up the steps and have that star staring me in the face. [The blue star flag mothers of servicemen were authorized to hang in a window.] He's very dear to me. . . .[I recall it also hanging for Paul in the window of the large front door during the Korean War.]

In the middle of September Dad went on furlough to Australia - Sydney, I think. He wrote afterwards: . . I had a nice time. It felt good to get back to civilization again. I didn't do much but run around with a few of the fellows on my crew. We went to shows, horse racing, boat racing, dancing and a few other things . . . When I returned . . . I found seven letters waiting for me and every one was from you. . .

|

| Mom also wrote of occasionally visiting Dad's guardians, Ed and Mary Chopot, pictured with Dad's older sister Evie (Charbonneau) Mallonee (1918-2012) in 1942 |

. . Remember the time we stayed up all nite and went to the five o'clock mass [when he came home the previous Christmas]? I have to chuckle every time I think of it. The next Sunday Father gave a long sermon about these young people who stay up all nite and go to an early mass. But it was fun, wasn't it. . . We haven't heard from Paul. That of course is understandable seeing that he is Somewhere in the North Atlantic. Before he left he wrote me his usual long letter, giving me encouragement on that - telling me not to do this and so forth [He was12 years older than Mom]. Then he told me where he was going. I really felt quite flattered because I was the only member of the family he told. I haven't told anyone - not even Dad. And I'm not going to tell until he is safely home again. Doggone it - they won't be able to say that it was a slip of my lip that sank his ship. . . .

Dad wrote in early October.

. . Just a few lines to let you know how everything is around this hot and miserable place. When it rains here, it really pours. . . I live in a tent large enough for six persons to live peacefully. . . Everyone has their bunks along the side of the tent, leaving room for a table in the middle. Oh, oh, pardon a minute while I kill a black widow spider that just now jumped on me. . . The place if filthy with them. They're not poison, but they sure give a guy a scare when they jump on you . . . [He must have been mistaken about the spider's genus, probably of the tarantula family. He told me in later years that, and this must have been at a different base, they had a path to a water hole through the jungle where they'd bathe, and a large shiny green spider built a thick web overnight across the path and one of the men walked into it. B-r-r!] . . . I'm . . . bunked opposite the main exit. There are many exits in this tent; the tent walls are propped up in order to have good ventilation, also leaving many exits for the fox hole, in case of an air raid from the Japs. We hear them coming, and run like hell for the fox hole, then pray that we don't get hit. . . Alongside my bunk I have a clothes rack, which consist of winter flying clothes, and working clothes. . . You may think it funny, darling, to have winter flying clothes here in the South West Pacific, but it's true. It really gets cold up there when you fly high . . . I know for sure it's below zero at times . . . but the change from hot to cold is what I like . . . It makes you feel so cool and refreshing up there, until it starts to freeze, then you want to come down where its warm, but of course you can't. You have to stay up there and take it for a few hours [his flights were averaging 5 to 7 hours, but toward the end, 10 and 11 hours] . . . I also have my mess kit for eating chow, an oxygen mask used for high altitude flying, which is getting plenty of use; a gas mask - I'm sure you've seen those things before, they look so gruesome, but they're a life saver. I also have two large barracks bags . . . a B-4 flying bag, packed with Sunday go-to-meeting clothing . . . alongside the clothes rack I have an apple box with two shelves in it. On the shelves I have toilet articles, gum, which I suppose is hard to get in the States, cigarettes, flashlite, and medical supplies. On top of this apple-box I have the most wonderful thing of all, which is a very beautiful picture of the girl I love, and boy, is she a knock-out. . . I sleep on an air mattress with no blankets needed, plus a mosquito net, which is spread out over the bunk at night . . . On the outside . . . there are two fifty-gallon barrels of water . . . a large tub for cleaning clothes and a foxhole . . . For recreation we have a ping pong table, a little poker now & then and a show three times a week, if the Japs don't bust it up. . . .

|

| One of five airfields at Rabaul. Note distance between Japanese planes, parked in revetments (excavations with earthen walls). From Dad's scrapbook. |

He was able to write to her on 25 October from the hospital, using American Red Cross letterhead, which I suppose he hoped was the tip-off, because he couldn't reveal what happened.

My Darling,

It's been a long time since I've written to you and I'm sure I had no intention of waiting so long. . . I would have written had I been able. I hope you understand. Everything seems to be fine from what I can make of it. . . Well, darling, I'll take good care of myself and hope to come back to you in one piece. I feel frightened at the thought of not coming back at all. But we all can't have sunshine and roses. Although I've never mentioned this to you before, for fear it would frighten you, but now I think you have the strength and courage to take it if anything should happen . . .

|

| Probably published in November, 1943 |

. . You brother came home. [Raoul Charbonneau (1920-2000), called Smoky by my dad, had enlisted in 1939, now returned from Panama.] I met him Saturday nite - in fact I went out with him. First we had dinner over at Mary's and Red's [Red being Dad's, Evie's and Raoul's double first cousin, and Mom's brother-in-law] . . .

|

| Omer "Red" Charbonneau (1916-1987) c.1950 |

. . then we all went out to the White House. We had a pretty good time - but not as much fun as when we went out. He is so different from you. He doesn't resemble you unless his face is turned away and then his profile is like yours. He is much quieter than you and he laughs very seldom. But I can close my eyes and I'd swear that it was you talking. He hasn't got twin devils in his eyes like you, but has got twin dimples (I prefer the devils). He dances very well and I did manage not to step on his toes . . . Then Sunday, he and Mary and Red came over for dinner. Mother and Dad like him, but they like you much more. And everyone was calling him Al. . . Mother said, "Al, do you care for coffee?" Then Dad said, "Pass the bread to Al." . . . I don't imagine I'll see him again, but it was nice meeting him. [After the war, Smoky married Mom's childhood friend, Jackie Merager. A few years after Dad died in 1994, Jackie died of a stroke. Smoky, then in his late 70s, spent much of his time at Mom's, fixing things, watching TV, and eating meals she cooked. They had a pleasant camaraderie until his heart gave out in 2000 at age 81.]

|

| Dad was injured on Oct 12. The telegram was finally sent Oct. 27 to Dad's guardian."Seriously injured" surprises me, but maybe he was. |

. . I was at the store when Aunt Mary [Dad's guardian, but no relation] called up. She told Mother and when I came back Mother was crying. She loves you very much, too - I knew right away something had happened to you. . . I felt my knees going weak . . .Then Mother told me your were hurt. Part of me died right then. I called up immediately and she [Aunt Mary] was all broken up. Oh, darling - darling - if you only knew how much we love you. Then everyone began calling up - everything was a regular bull ringing affair. But I went to work. I had to go because if I just sat around, I'd go insane. . . I didn't tell anyone but a very dear friend [Monnie] - but she told them and they were so thoughtful and considerate . . . Oh, my darling - if only I could be there with you . . . to hold you in my arms and make you forget what you've been through. We'd forget everything and everyone but us. and we'd think and talk only of our future in our little apartment - and all our dreams and hopes . . . .

Oct. 29, 1943

. . [after writing about her rediscovered love for Dad] Don't tell anyone but I'm skaired - uh-huh - I'm a coward at heart. But nobody's home and they won't be home for a while. You see Uncle Gus [Grandma's older brother who lived with his sister Laura on a farm outside Addy, WA] is terribly sick - his horses ran away with him and drug him for a long time before they could stop them. And he's hurt pretty badly - he's almost seventy and there's not much chance of his pulling through, but Mother and Dad went up there [Uncle Gus survived, but had head injuries and eventually dementia] . . . and I'm all alone. This old house fairly creaks with strange noises. Wish you were here to hold my hand . . . Know what, darling - I got my first [war] bond today - I've been buying stamps and I finally got my book filled and I cashed it in and now I've got an interest in this land of ours. We'll cash it in ten years from now and put Junior through college . . . .

|

| Augusta Smith (1876-1965) and one of his beloved goats, c.1949 |

Nov. 1, 1943

. . Before we went to bed we gorged ourselves with scrambled eggs and bacon. It's funny how when it gets dark those of the less braver type simply wilt. Well it was twelve when we got home from work [Monnie worked at Western Union, too, and would become Mom's bridesmaid] and we didn't get to bed before two. . . we were chattering away . . . but then our blood froze because it sounded just like some heavy person coming up the outside steps. Wow! Did we freeze then. Very timidly we turned the porch light on and found out it was only the screen door thumping against the side of the house. But that settled it right there - we were going to protect ourselves even if all the doors had triple locks on them. So, don't laugh, dear, 'cause it wasn't funny then - we took a butcher knife and a flashlight and a rolling pin to bed with us and, oh, yes, I forgot - we also took the dog to bed with us, too. Every five minutes we'd sit up - and look at each other and say in a horrified whisper, "What was that?" . . . [W]e even scared the dog and he spent the night sleeping under the bed . . . .

Mom finally got Dad's letter of 25 October on Red Cross stationary on November 15. She wrote the next day.

Nov. 16

. . This morning I got up and went to six o'clock mass. O-h-h-h it was beautiful - the world I mean, at that time of the morning. It was still awfully dark, so I made Tuffy (the dog - remember?) go with me. [St. Aloysius was five blocks away]. Not that I was afraid or anything - you understand - but I took him along just for company. Ha! . . . All the leaves were heavy with frost and the light from the street lamps shown on them, making them look like a million jewels hiding in the grass. The air was so crisp and cold that I tried to blow smoke rings with my frozen breath . . .There were very few people [at mass] and there was a sacred beautiful silence that can only be found in a House of Worship. The altar glowed with candles and autumn flowers and the air was heavy with incense. Behind me the organ played in a soft whisper. Kneeling there I felt so happy and oh so very grateful to God - because it was yesterday that your letter came . . . That's why I went to six o'clock mass . . . because I wanted to tell God right away how oh so very thankful and grateful to Him I am because the love of my life is getting well again. You see, He knows how much I love you. . . .

Sometimes their letters took a month to reach the other. A letter Dad wrote on November 15 was passed by the Army censor and postmarked November 28. And that was the day Dad went back into action on a bombing run to Wewak. He didn't write about the October 12 crash until January 1944, when the skies were finally being cleared of Japanese planes between Port Morsby and Australia. I'm jumping ahead to tell that story.

Jan. 15, 1944

. . Here is the little episode I wasn't able to tell you about some time back. . . We were off to bomb Rabaul, got over the target then everything happened at once. Before we knew it we were going down. We were pretty high and had a long way to drop, so if we lengthened our dive we would get out of the Japs' reach when we crashed. It was the most gruesomest feeling I ever had in my life. Knowing you're going to crash and you can't do anything about it. All I could do was pray and let happen what may. The water came closer and closer to us until we hit it. I could feel myself being thrown out of the ship, then everything went black. When I woke up, I was some place in the water with the fish. I finally reached the surface and got my breath back. I then made my way to the life raft. We started paddling to a small island about a mile away. After reaching the island we applied first aid to ourselves, ate what little food we could, so it would last longer, for we had to get well before we could move on. [As I recall from his telling it years later, on their way to bomb Rabaul one of the four engines conked out. The pilot asked for a vote whether to continue the bombing run or return to base. The men voted to go on and drop their bombs - returning to base with a full load of bombs was also dangerous. After dropping their load and turning around to head back to base at Port Moresby, a second engine stopped. Unfortunately, it was on the same side as the first dead engine. Hoping the Japanese didn't intercept his message, the navigator radioed their position to the Royal Australian Air Force as their pilot glided the plane as far as he could. They landed on a coral reef, which ripped the belly out of the plane. The crew was flung out and Dad came to underwater, which was actually about waist-deep. Disoriented and unable to swim, he pulled his Mae West (life vest) and popped to the surface. The man most hurt had a broken back.] That night about 7 p.m. a plane came diving overhead. I thought at first it was a Jap plane. But I'm glad I was wrong. . . The plane was a friendly and dropped us supplies. [A few of the men swam to a nearby island - a tiny one - and found the skeleton of an Australian flyer sitting against a palm tree. That night as the men were trying to sleep, Dad felt something nibbling at the blood on his face. Rats had smelled blood from miles away and had swum to the island. The men stayed awake the rest of the night.] The following afternoon we were rescued by the Australians [a float plane] and brought to a hospital. I remained there for the following six weeks. . . . [The coral had deeply gashed him along his shin bone from knee to ankle. His face was torn open from his lower lip down his chin; its scar formed a deep line that forked at his chin. When I was small, I'd run a finger down that scar. There may have been other injuries I didn't know of. Six weeks hospitalization for deep lacerations seems too long now, but the doctors must have been worried about infection. Penicillin was being used in the military by then, but it was still somewhat experimental.]

|

| Dad's crashed B-24 on the coral reef. Appears the tide was out when the photo was taken, possibly by the plane that dropped supplies or the one that rescued them. |

|

| Rabaul Caldera (volcano) today |

Dec. 15, 1943

. . Paul is home - really home I mean - he'll be here for Christmas, too. Honestly, I'm so happy. He came in Friday nite and no one knew about it. Then Saturday he came over and spent the day with Mother and Dad. Of course, I knew nothing of this. So Saturday nite after work I was running to catch my bus and I bumped into an old friend - and he said, "Sa-ay, when did Paul get in town? He certainly looked snappy in his uniform." I asked him when he had seen him and he said, "Friday nite." Boy, was I boiling. To think that he had been home two whole days and didn't even call up. . . Sooo-oo-o - Sunday morning I got up and went to an early mass before the folks got up. When I came home there sat Pop with a smug grin on his face. He said, "Know what?" And before I even thought, I said, "yes - Paul is home." Ho- you should have seen the startled expression on their faces. They weren't going to tell me, the rascals, until he walked in on me that day. Oh-h-h - did I ever feel like a heel. But anyway, around noon Junice called up and said that he and Denny [Mom's other older brother married to Junice] were on their way over. . .

|

| Denny Raney (1915-1991) and his namesake, Dennis Jack Raney, c.1946 |

. .She no sooner hung up when they were coming up the walk. When I saw him I had the awful urge to run and hide because all of a sudden I was overcome by an unusual shyness. Then he opened the door and with one swoop he had me in his arms. And - oh! I was so mad at myself. I swore up and down I wouldn't cry - but the minute I saw him - we-ell - I was sobbing on his shoulder. I really felt terrible until I peeked up and saw tears running down his cheeks, too. He's been on the North Atlantic, but he received his papers and now he'll be on the South Pacific. Wouldn't it be wonderful if you two ran into each other? . . . He's so terribly thin and he looks so tired. He made my heart ache when I looked at him.

It hardly seems a year ago Christmas that we were together. Remember Christmas dinner and you and Paul were so silly . . . and everyone was making so much noise you couldn't think straight. I couldn't anyway - I was rather dizzy from the wine. It will be the same this year - Noise! Noise! everywhere - everyone will have just a little too much wine - everything will be the same - only you won't be here. But I know every one of us will be thinking of you and knowing that it won't be so very long before you are with us again . . . .

On 13 December, Dad's 403rd Bombardment Squadron of the 43rd Bombardment Group was transferred from Port Moresby across Papua, New Guinea to Dobodura. A 15-airfield complex had been built. It was bombed by the Japanese as recently as October 1943. And, yet, that same day he and his crew were in the air six hours on a bombing raid to Gasmata, New Britain.

Dec. 21, 1943

. . I bet you're getting tired waiting for me. I'll make it home one of these days. I wonder what it'll be like at home. They have been flying the pants off us lately. Boy, am I tired. I feel like I could sleep for a week. I only wish I could [he would have trouble sleeping the rest of his life.] Well, there's one thing for sure, I'd hate to be in Tojo's shoes, I don't think he's had any sleep for months. . . .

|

| Grandma & Grandpa's house in winter |

. . What a mad house this was. You know what it was like a year ago - we-ell it was twice as bad this year because all the kids were one year older. [That was you Pat, Jack, Sandra, Chuck, Rich, and Jimmy. Nancy and Frank, too, rest their souls]. . . And after everyone has now gone to bed - and the house is quiet and peaceful - I've turned off the lights and turned the tree lights on. The tree is still in the same place - the swing is still in the same place - I'm still in the same corner of the swing. But where, my Darling - where are you? . . . You're stretched out on the swing with your head in my lap. And I'm running my fingers through your hair - and we're laughing and talking about the future - just as we did a year ago tonight. You're here, my Darling, if only in my thoughts . . . .

|

| Mom's New Year's Telegram to Dad. It was received at Brisbane, Australia. Then mailed to New Guinea, I suppose. |

. . We tried to be so gay New Year's Eve. Two other girls from the office and I. We worked until twelve. But I don't think any of us minded very much . . . Both of their men were away, too, and so we sort of kept together. I had a quart of Port - a gift from Dennis [her brother Denny]. . .

|

| Mom and her future bridesmaids Monnie and Betty |

Feb. 9, 1944

[Mom's response to Dad's complaint that he hadn't received any letters for a while] . . I will try to write to you every other day from now on. The only time that I can write is when I come home from work at nite. It's about twelve-thirty then. First of all I must read the paper and catch up on all the scandal - then I round up a sandwich and a glass of milk . . .'cause I can't go to sleep if I don't eat something. . . Then I wash my face and brush my hair and wash out what needs to be - and by that time it's two o'clock and before I have half a letter written I doze off . . . .

|

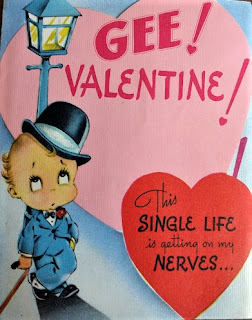

| Mom's Valentine sent to Dad early in 1944 |

. . Mary and Junice are working for the tomorrow of America. Two future presidents are on their way. That will bring me up to being an aunt - let me see - uh-huh - eleven times. Golly - "and may our tribe increase." I feel sorta left out of things. . . . [Junice would have Mary Jean and Mary would have John - may he rest in peace.]

Dad was changing, sounding angry in his letters. He probably was drinking heavily on the days he wasn't flying, and that's when he'd write to Mom. He wrote some odd letters, using a thesaurus to substitute archaic words for common ones. He called her Valentine "quaint," which pleased her not at all. In his defense, he was not a reader as Mom was, so didn't understand the subtle meanings of words. She wasn't writing as often. As she later told me, "I was writing to five servicemen overseas, one in a German POW camp." And she was tired, seldom getting a day off from work. And another man in uniform had entered her life . . .

. . Well, I believe you know as much about this war as I do, so there is no need to go into that subject, besides I dislike it immensely . . . I think I'll go on a toot when I get home. I'm going to get so tight that I'll squeak when I walk. What do you think of that? . . .

On 12 March, his unit was transferred up the New Guinea coast to Nadzab (see map).

March 17, 1944

. . We've been completing our missions with little opposition for some time. If this keeps up, no telling how soon the Japs will bail. They're still a tough customer and hard to deal with . . . If the post-war loan is voted in for the overseas soldier . . . We could get a nice home, here's hoping. . . .

[As mentioned earlier, Dad was a tail gunner. The B-24 bomber was a long-distance bomber that flew sorties in groups. P-38 fighter planes would accompany the sortie part of the way, but didn't have enough fuel to go the distance, and would have to turn back to base. It was then that Japanese zeros came at the bombers. I never asked how many times his plane was attacked. Still a child, I asked, "How many zeros did you shoot down?" He answered that he knew he shot down one, and perhaps two. Gunners on other ships were firing, too.]

April 24, 1944

. . It's a little fantastic . . . what [your letters] can do for a person here in the jungle, and in the blue battlefield . . . the thought of your last letter would boost my courage, then I would have more confidence in myself . . . I'm getting so lonesome for you and your letters, I'm really getting scared to fly. Just think, it'll be a year the 22nd of May that I've been in combat . . . My nerves are beginning to crack. But I can't quit; that would prolong my stay in this God forsaken land, and I want to get home to you, Darling, as soon as I can. I've got 46 missions over enemy targets, with 265 flying combat hours. The goal is 300 hours. I hope to finish in 7 more missions, then I'll be coming home. I was sent to Australia on furlough for my own good. I was sure glad to get away from combat for the 12 days that I was gone . . . I guess it will be May by the time this letter gets to you. Spokane in the springtime with its sweet fragrant smell of flowers everywhere. How I wish I were there to take in some beauty for a change . . . I'm lucky to hold the pen somewhat steady . . . .

She wrote an undated letter toward the end of May when the lilacs were in bloom

. . I'm so very happy you got a furlough to Australia. You needed a rest so terribly much. I'm sure you feel much much better now, don't you? What did you do there? Did you go again to the races and boat riding and dancing? Sounds fun, huh. Bet that is what you really needed - fun, relaxation, and next to home there isn't a better place than Australia - or so I've heard. . . You should see our Victory garden. It's really funny - but nice. The beans and hollyhocks are growing together - and the pansies and onions - and larkspurs and peas. Dad and his artistic ideas. . . Each time you're up there, you're not up there alone with the enemy. He is up there with you. God will never leave you. Pray often and remember that this madness cannot last forever. There will be a turning point . . . You're strong, Al. You can face it. You've shown magnificent courage in [the] face of physical danger, that I know. Don't let this invisible danger threaten your strength. Fight it - and you'll overcome it. Believe me, Darling, you're not a weakling - you're brave and strong - you won't fail - I know you too well. So, carry on, Darling, and remember my prayers are behind you, fighting with you . . . .

Dad had hoped to come home when he reached 300 hours of combat flight time, but because there was a shortage of combat replacement personnel - Europe was the main focus now - he was held for four more missions, 340 hours on 55 missions.

|

| Dad's compass, his silver bomber wings, a water-proof nickel match container, and his leather log book that fit in his pocket. |

|

| Dad's log book, showing target, date, flight time, accumulated hours, and mission number |

. . Altho I haven't heard from you for some time, I feel it my duty to write and let your know how I'm getting along. . . We're pushing the Japs back as best we can. I'm sure they're beginning to understand that they're no longer an unbeatable race . . . Between the food, heat and flying conditions, I endeavor to keep in as good shape as possible, although getting "skinny in Guinea" is far from being perfect. Not long ago a few of us went boar hunting, found two, killed same. What a delicious dish they made. Not that we were versed in the art of cooking, but we get along . . .

Had a rather exciting mission the other day. While over the target, an engine was shot out of commission by ack, ack. These Japs are good in that respect. It wasn't my first experience of that kind. At times, I've found myself wishing in time of danger that you were near to give me confidence and support, that I might carry through, what was expected of me. . .

. . I've quit drinking. My improvements are astounding. I can recall the time when I'd felt better dead than alive. I don't know why a person gets to drinking over here, unless it's because of the dangers of war. I've been in a daze ever since my crack-up. It's about time I woke up. [He wrote that he hadn't gotten a letter since the one dated April 4.]

Dad's last 5 missions, from 27 May to 17 June were over the small island of Biak, on the western side of New Guinea, now belonging to Indonesia, a Japanese stronghold honeycombed with caves . In reading about the Battle for Biak, I realized the bombers were dropping bombs close to American forces, probably in the far north part of the island where the main airfield was. HERE

He didn't write Mom that he was coming home or, if he did, the letter is lost. He didn't fly home, but came by ship (to California, I think). He crossed the equator on 31 August 1944 on the U.S.Army Transport Cape Flattery.

Mom finally wrote on July 9, 1944. Although I would think he had left New Guinea before it arrived, there is no forwarding address on the envelope.

. . Quite a bit of time has elapsed since [I received your] last letter - Really too much time and I'm almost ashamed to write this. I've been down to California for awhile and time slipped through my fingers terribly fast. I went down to see Paul graduate. [He'd gone back to Merchant Marine School at Alameda for a few months of advanced studies to gain a promotion.] It was really an adventure for me because I have never traveled anywhere alone - but it was fun and I enjoyed myself very much. [If memory serves, she took a bus down and back. A sailor sat with her and fell asleep with his head resting on her shoulder.] But as for California - well, there really aren't any words to tell you my intense dislike of the place. It's much too cold and disagreeable for my liking. . . I was around Frisco, Oakland and Alameda. I really don't know which was the worse, the sand fleas or the cold weather. But, anyhow, I'm back in sunny ole' Spokane and nothing can make me budge . . .

Again I am about to become an Aunt. Never let it be said that Mary Agnes isn't doing her part towards the future Americans of Tomorrow. Naturally everyone is excited in the family - they have gone so far as to lay bets with each other concerning the sex of the child. Mary wants a girl very much since she has two boys already. Dad bet her a new dress it would be a boy and she bet him a new hat that it's going to be a girl. Honestly, this family. . . Just sort of keep your fingers crossed that everything will turn out alright. That above all is the main thing . . . [It was a boy, John Charbonneau. Mary would get a girl on her eighth try, and afterward have another boy.]

|

| Mary Agnes (Raney) Charbonneau (1921-2003) c1946 |

|

| Dad soon after returning home |

. . H'lo Man O' my Heart - How can I write this letter - my heart won't be in it - I left it home with you - what a temptation it was not to turn and run back into your arms - But - I didn't, unfortunately. Right now it's five to three (in the morning, not afternoon) We three are writing letters to our "men" - those dear kids. They wouldn't leave me alone until I told them everything from the minute I saw you until I left you. . . I'm still up in the clouds - I have a funny feeling I'm going to stay up there a long long time.

Everything went very smoothly at the office - they were grand about it. I was prepared for the worst. But I'm still very much alive. [She must have left Seattle as soon as she got a phone call - maybe on her day off.] . . . Know what is on the radio now? It Had to Be You - that's so right. Know how it goes? "It had to be you - it had to be you - I wandered around and finally found - Somebody who - could make me be true - And even be glad - just to be sad - thinking of you - Some others I've seen - might never be mean, might never be cross - try to be boss - but they wouldn't do - Nobody else gives me a thrill - For all your faults I love you still - It had to be you - wonderful you - It had to be you." See how right that song is, Al. It always was - it always will be you. I love you - I love you. . . .

It appears he went over to see her in Seattle in early October, for she wrote October 7, 1944:

. . [H]ow terribly lost I feel without you - tonight without thinking my eyes went to the curb. I knew you wouldn't be there - and yet the disappointment at not finding you waiting there brought tears to my eyes. How much do I miss you? So very much . . . I can't quite believe that next month we'll be married. . . I just took my nightly shower - now I'll go jump in my bed and dream of you. Hey - you'd better be there in my dreams waiting for me or you'll be sorry - Yes, you will . . . .

|

| One of a series of "glamor" photographs Dad took of Mom a few days before their marriage |

|

| November 20, 1944 |

|

| Dad's hat and Mom's veil |

No comments:

Post a Comment